Not too young to die in prison

People under the age of 17 are deemed by the law too young to smoke, drive, buy alcohol, or go to an R-rated movie. They are too young to vote, serve on juries, or get married under the name of God, without parental consent. Yet, they are not too young to die in prison. The fact about certain serious crimes in the U.S. is this: it doesn’t matter how old you were at the time of the crime. If found guilty, even a very young person can land a life or even a life without parole sentence.

According to the Equal Justice Initiative, 11 states have no minimum age for being tried as an adult: Alaska, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia. Other states allow prosecution as adults to start as young as 10, 12, or 13 years old. And for that reason, juveniles who are sent to prison for life terms are aging and even dying in U.S prisons with little hope of ever being released.

I know all this because I am one of those juveniles. I committed my crime at the age of 16 and entered a maximum-security adult prison in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, at the age of 17. I am forty-nine now and I would give anything to prove myself worthy of a second chance.

I am sure you are asking yourself, “If she committed her crime in Oklahoma, how did she end up in a California prison?”

I am here on interstate compact, a system that allows prisoners from one state to be housed in another. I am still under Oklahoma laws but I share the pains of juvenile imprisonment with many people, no matter what state they are in. We do not have data on the total numbers of people currently in U.S. prisons on life terms who were sentenced as juveniles. But here at CCWF we have approximately 17 juvenile offenders who were seventeen and under at the time of their crime.

It’s a painful realization for a youthful offender to mature into adulthood and realize that the only life they will ever experience is behind bars. The majority of us were not old enough to graduate from high school. Most have never been on a real date, or gone to an amusement park. We’ve forgotten what it is like to go see a movie in the theater. Many of us came from poor or low-income families who could not afford many things, including an attorney. We ache inside for all the things we have never experienced. We did not know what the world was truly about or who we could or would eventually want to become.

In addition to this heartache, juveniles in adult prison often face frightening treatment. They are exposed to extreme levels of physical, sexual, emotional, psychological, and social control abuse. These juvenile offenders are immature, young, and easier to victimize, manipulate and control. In my home state of Oklahoma, there are children as young as thirteen sitting in the maximum-security prison for women called Mabel Bassett Correctional Center. I have witnessed these children (including myself) humiliated, used and taken advantage of by professional career predators.

Even though some long-standing federal legislation intended to protect juveniles does exist, there is only so much it can do. The Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act, originally passed in 1974 and amended regularly (as recently as 2020), is supposed to keep children as much as possible from long-term confinement in adult facilities and when they are placed there, it should be under “sight and sound separation.” In other words, away from psychological abuse, physical assault from adults, and from isolation. What is lacking is a moral obligation to care for the mental, emotional and physical safety of these children, rigorous protection and a long-term solution for possible release for these teenagers sentenced to life imprisonment.

The U.S. is unique in this way. It’s not a secret that ours is one of two countries (with Israel) that sentences adolescents to spend their lives in prison. In December 2006, the United Nations took up a resolution calling for the abolition of life imprisonment for juvenile offenders. The vote was 185 to 1, with the United States being the lone dissenter.

What the rest of the world acknowledges is this: Teenagers are different from adults and should not be treated as equals. Experts in psychology who have done research on young people say that when compared to adults, juveniles are impulsive, aggressive, and emotionally volatile. They are more likely to take risks, more reactive to stress, and more prone to focus on and overestimate short-term payoffs. Due to their lack of maturity, teenagers underplay the long-term consequences of their actions. They’re likely to overlook alternative courses of action. In most serious cases, these teenagers were vulnerable to peer pressure, not just from their peers but by adults who manipulated and used them for their own gain, to do things that were illegal and life-costing.

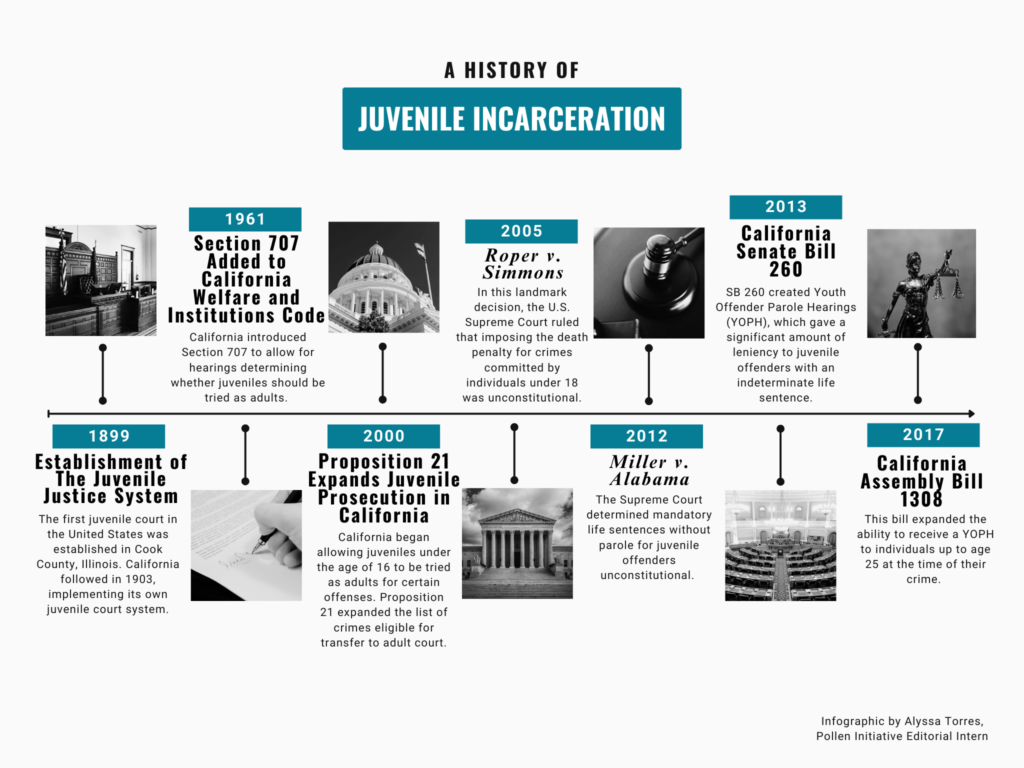

Temple University Psychology Professor Laurence Steinkey is often cited for saying, “The teenage brain is like a car with a good accelerator but a weak brake. With fast powerful impulses under poor control, the likely result is a crash.” Steinkey contributed to an American Psychological Association brief for the 2005 case that ultimately brought an end to the death penalty for crimes committed before age 18.

The extension of their argument is that a young person’s vulnerability and comparative lack of control over their immediate environment means they have a greater claim to forgiveness than adults, for failing to escape from destruction.

Many organizations have been fighting this battle for years: Initiate Justice, Children’s Rights Division of Human Rights Watch, Sister Warrior’s, Restorative Media, etc. I hope that one day they will triumph and save our youthful offenders from a fate of confinement for the rest of their lives.

There has to be a more humane way to approach juveniles who commit serious crimes other than locking them up and throwing away the key. House of Representatives (H.R.) Bill 3305: Juvenile Justice Accountability and Improvement Act of 2011, was one of the first of many, submitted by the House, introduced by Senator Scott of Virginia.

This H.R. Bill and the ones that have followed, would establish a meaningful opportunity for parole (or a similar type of release) for child offenders sentenced to life in prison. It would become available to youths who committed their crime(s) under the age of eighteen and who are sentenced to life in prison. For juvenile offenders like me who belong to a states whose legislation does not yet account for the teenage neurological development into account with their legislation, the way the California has with Senate Bills 260, 261, and 263, it would be a dream come true for so many juvenile offenders who has spent many years, praying for a “second chance” at life.

I know that many people, especially victim’s rights groups, feel there are crimes so terrible that only life sentences are a fit moral response for these youthful offenders’ behavior.

However, when it comes to children, who likely established their behavior from the adult role models in their life, a life sentence is just as effectively a death sentence carried out by the state slowly over a period of years.

The good news is that the total number of people under the age of 17 languishing in prisons and jails has been decreasing for a long time. The most up-to-date numbers from the Bureau of Justices Statistics report that the total prison population who were juveniles declined from 0.2% in 2002 to 0.02% in 2021.

I hope that one day society will find it in their hearts again to also give us juvenile lifers a second chance. Please do not let life in prison become the only life we ever know or live. Prison is a horrible, rotten place full of darkness. Nevertheless, in the depth of this darkness, there are little spots of light. We call these little spots of light: faith, hope, forgiveness, and the dream of a better tomorrow.

The article written by Heather Rosemary Miller, “ not too young to die in prison” is written beautifully. There are so many facts. It’s heartbreaking. Informative gives a true understanding of how unjust. The justice system is in the state of California for our youth. Restorative justice should be used on any juvenile, not life without the possibility not life. It is inhumane to give a child of life sentence. Heather Rosemary Miller you did a wonderful job you articulated it perfectly applauds to you and my prayers as well God bless you, Heather.